By Emilia Brookfield-Pertusini

I shut my eyes and all the world drops dead;

I lift my lids and all is born again.

(I think I made you up inside my head.)

– Sylvia Plath, Mad Girl’s Love Song

On this day, in 1963, during the coldest winter in living memory, a woman died. Her name was Sylvia Plath.

So, there she is, the American genius, sent to Cambridge on the promise of extraordinary, who by the age of 30 would change English poetry for a damnable good. Boyfriends numerous, looks renowned, tongue sharp. She is Miss America – coming to our shores to dazzle us out of post-war grey prose, and into the neon lexicon of exceptionalism. A double exposure of both catastrophe and creative flair. A bright tragedy, burning brighter, brightest now. Shadowed now, by the 1980’s answer to poet laureateship, and a gas oven.

This is not a piece of anti-Hughes venom. This is not a piece of excuses and blame. This is a piece against sensation. This is not a fairytale. There is no winner, no villain, no dastardly plot; this is vast, violent living. A prose we can only hope to grasp, with each word holding a negative side, a double exposure of intention and sight. Words left unsaid. Double Exposure, diaries, drafts burnt. This is the reality of a tragedy; we now live in the fallout. The world is utterly changed by this, yes, but this is not a world ending story. This is life in its most phenomenal form.

It would be naïve of me to say that Plath’s marriage was complicated. It would be more naïve of me to say that it was brilliant. From the moment of its inception, on the 25th of February 1956, in a smoky poetry-infused evening, a terrible beauty was born. Plath bites Hughes cheek, much to the dismay of Shirley, Ted’s girlfriend of the time, whilst Hughes steals Plath’s earrings. This was Hughes’ launch for his Saint Botolph’s Review, a stab in the dark for an emerging poet in an upstairs room in Cambridge that would change the course of poetry forever. Even their passionate meeting, a fatal poetry; the apple-cheeked bite that damned the soul, thwarting the fate of man. An explosive longing and ruinous sentencing, at once. It is easy to see why the pair came together with such intensity. The pair would later marry on ‘Bloomsday’ adding further fuel to the fire of their literary perfection. Two poets, both alike in dignity, matched their courage, and embarked on a love that violently bit away for decades to come. With such intensity steeped and stewed in literary coincidence and allusion it is easy to glamourise, pine, attack, and mythologise the events that surrounded this pairing. The myth that has surrounded a marriage, a union simply brought on by bureaucratic necessities, has terrorised the literary scene since, dividing and demonstrating the passionate love begot from Plath’s prose within its captivated readers.

To read The Bell Jar for the first time, as I did like every other lonesome 13 year old girl, is to bear the burden of a beating prose. Plath’s poetry refuses to retire when in novelistic form, each sentence upholding a thumping march towards utter depraved bleakness. ‘I am, I am, I am’ becomes not only the echo of a worn out heart, but the attitude we take on when immersing ourselves into the dazzlingly twisted light of Plath. We become Esther, we take those miseries to heart, each assertion against an unjust, wretched world clarifying our own world view. We all have a fig tree growing in our heads, whose branches have always been braying against each battled decision we must take. To be met then, aged 14, with Ted Hughes’ seismic war poem Bayonet Charge, so vastly different yet equally enrapturing as Plath’s own war of words, in my GCSE classroom and the chaotic contextual notes that come with it, shattering. The Plath I had found solace in, who’s writing resonated in such an extraordinary echoing concert of nuances, had been with him? The magical meeting I have just described is destroyed by such a crushing piece of sensation. The literary clad love is stripped and moulded into a story of abuse and blame, furthering the dramatisation of Plath’s life. The monolithic marriage glossing over the exposures that lie beneath, glossing over Sylvia herself.

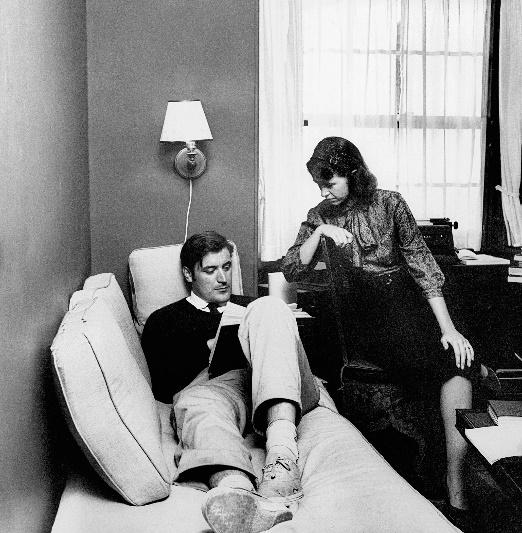

Teenage loyalty follows Plath, even in her non-teenage followers. Her mythic haunting of the canon has tormented her legacy within both pop culture, Hughes’ life, and the literary scene. The fascination with the Hughes/Plath union has spiralled into a morbid mutilation of itself, with stubborn opinions shadowing the past. The understated and overlooked element of their relationship, what to me is the Rosetta stone that unlocks the intensity of both their marriage and poetry, is their closeness. Apart from Sylvia’s Michaelmas term in 1956, when they lived apart in fear of the Newnham College seniorities, they often didn’t spend more than half a day away from each other, living during the climaxes of their marriage on the road across America together, or in a secluded part of Devon. Their writing is in constant conversation with each other – each partner lurking in the lines of the other’s, and often they were in conversation with each other whilst writing, editing and guiding each other.

Image courtesy of James Coyne, 1958

‘Oh, he is here; my black marauder; oh hungry hungry. I am so hungry for a big smashing creative burgeoning burdened love: I am here; I wait; and he plays on the banks of the river Cam like a casual faun’ – Plath, Unabridged Diaries, March 10th 1956

Even in its all-consuming poetic brilliance, the poetic candour of this relationship is embellished. The ‘Bloomsday’ ceremony, a coincidence. The biting encounter, a drunken flurry. Plath’s perspective on the pairing, even in the private confines of her rigorous kept journal, is ever poetic. Nothing is casual coincidence. From Plath’s private notes on Hughes, throughout their relationship, we see her use her life and mind as a way to explore the poetic boundaries of her confessional style. Her life is her muse, yet, like all muses, it was the way in which she captured it that cemented it as a grand, glowing, myth, not the object itself. Their married life was fairly ordinary. There were holidays, work parties, and hobbies taken up in harmony. Household business went unorganised and mounted. Worries about money came and went. The marriage failed, as marriages do. People betrayed promises, as people do. They shared a closeness that couldn’t be contained in the boundaries of the ordinary marriage they attempted construct. It is a sad story, made sadder by Hughes’ attempts to reach Plath during her final days, but this is not an extraordinary story. It is a marriage mythologised and a life absorbed.

Reduced to a moment of unimaginable pain, her words misconstrued, the marriage’s pain magnified; she is yet to exist as just Sylvia. She has become a teen idol – appearing in Lana del Rey lyrics, appearing alongside Kat Stratford in 10 Things I hate About You, appearing in quotes and illusions as Angelina Jolie wreaks an effortlessly cool havoc on Plath’s own alma mater McClean Hospital. This is a lot to attach to one 30 year old, catapulting her name beyond the canon and into the canonised veneration of cultural icon. By attaching so much to a life and works, things get lost. The complicated tones of discussing Hughes and Plath are reduced into tangible volatile forces, the complicated nature of Plath’s own mind and poetry is reduced to throw away lines that carry a weight beyond their intention. Plath becomes an object, part of the make up for some aesthetic that is abstract from her and unrecognisable from her own time. Her confessional style that opened the world to the workings of her mind has now bore a life of its own, trapping her in those poetic moments, obscuring the life that existed around them.

Attending a star-spangled poetry class with Anne Sexton and taught by Robert Lowell in 1959, Plath ventured headlong into the confessional form. The art of confessional poetry is a controversial form, one that strives to unleash the inner most perspectives and psychologies from the poet onto the world, teaching the reader about escape in a most intimate form, straying away from the abstracted, open form of poetry that came before it. Plath’s poems explore her own mind, they don’t attempt to convince us, but rather to feel beyond the surface. She captures the double exposure of humanity, the identification of the world, and the terrible beauty that brays persistently beneath it. There is no simpleness, no stillness; there is more to the world that meets Plath’s eyes. This double exposure identification has left Plath herself double exposed, with her writing being used to further prescribe her with her tragedy, condensing her to her most profoundly rapturous creative outbursts.

All these iterations of Plath leave her in a manipulated, mutilated legacy. For some she will be dying forever. Her suicide being the morbid fascination that pins her manic adorations and depressive tirades together. After all, death has always mystified our interests more than life. For others, her bruises will never heal, as she gets wheeled out to puppet the cries against Hughes, her mouth filled with venom that corrodes the love and artistic companionship that existed alongside the bitterness and pain until the end. Sometimes, she’s a bright girl from the States who took the poetry world by storm, carefully typing away with thesaurus on her lap, other times she is the tortured poet writing in the dark in an unbreakable artistic frenzy. All of these should exist at once. Each glimpse of Plath pertains to a negative exposure – a double exposure of a rich, verbose life. These glimmers of life should be respected for their beauty and magnitude, whilst the urge to hold them forever, to understand why the light breaks through the darkness thus, is to destroy and falsify what is there. We must learn to be content with the Plath we know briefly, be fascinated by what she is, not what she was not, refusing to let our love for her madden us to transform Plath into a figure we make up in our heads.

Image courtesy of Newnham College, Cambridge

If the moon smiled she would resemble you. /You leave the same impression/Of something beautiful, but annihilating’. Let Sylvia close. Let the ideal of a mythic poetess live in the imaginary. She can only resemble our hopes and dreamy projections, but her life leaves a lingering presence, ‘something beautiful, but annihilating’ its shocking, ordinary reality.